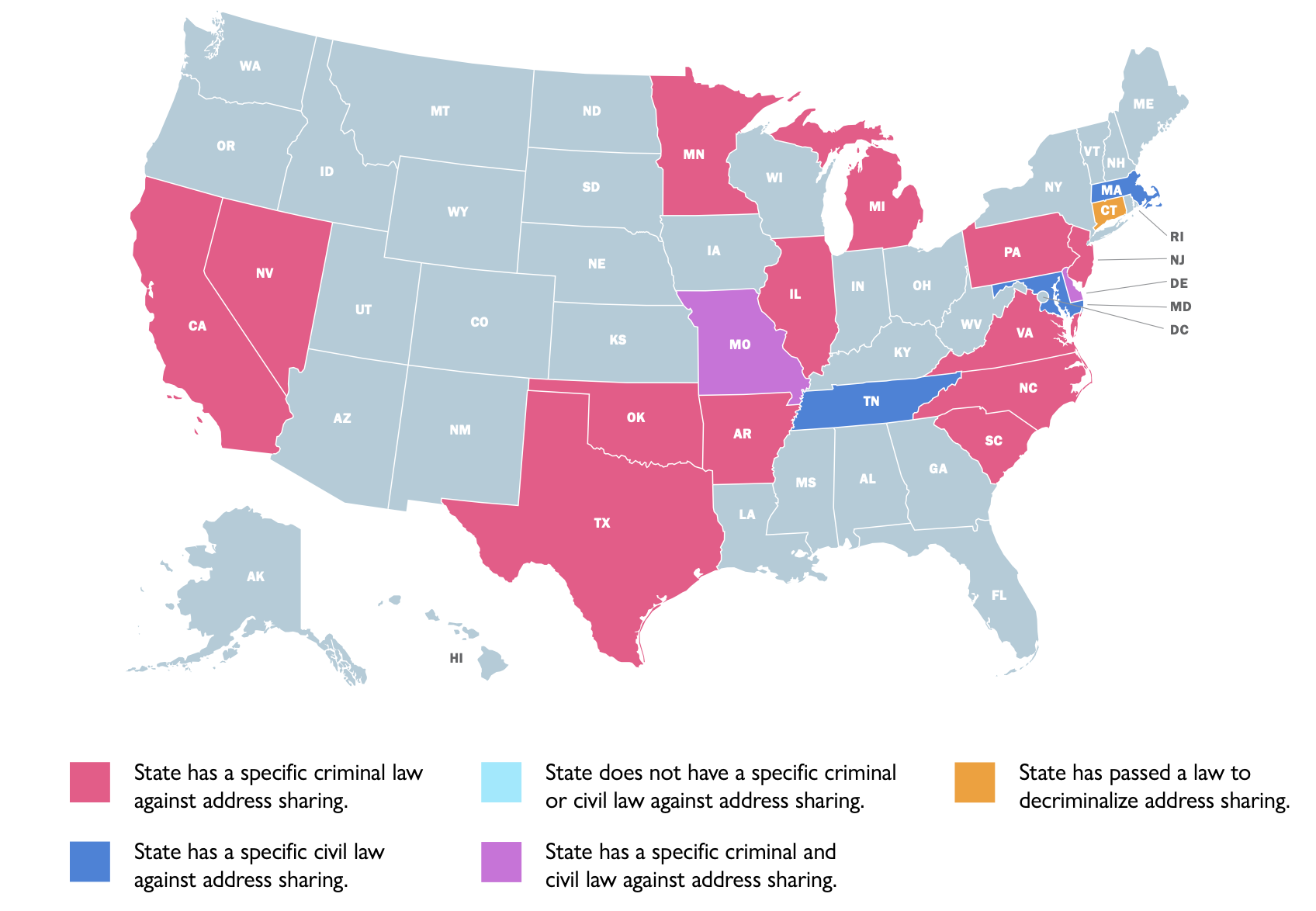

In nearly half the states in the country, parents risk criminal prosecution — and jail time — if they use a false address to get their children into a better school, a new report shows.

Georgia is one of them, something Valencia Stovall, a former state legislator, tried to change in 2020.

She sponsored a bill that would have allowed a parent to use an address outside their attendance zone as long as the person living there gave permission. The legislation also would have exempted such parents from fraud or forgery charges.

“No parent wants to drive an hour and a half in traffic to get their child in another school,” said Stovall, a Democrat who supports school choice. “They are thinking about the future of their children, and they know education is the key.”

The bill didn’t pass, and to date, only Connecticut has decriminalized what the report — published Tuesday by nonprofits Available to All and Bellwether — calls “address sharing.”

In a post-pandemic era where more parents are shopping around for schools that better suit their children’s needs, the authors hope other states follow Connecticut’s lead. According to co-author Tim DeRoche, who has previously written about exclusionary attendance zones, the issue falls under the radar because it’s more common for districts to “quietly kick the kids out of schools, using the threat of prosecution.”

When districts do involve law enforcement, criminal charges and stiff fines often land on the backs of Black, Hispanic and low-income families, he said. The report points to a 2018 public radio investigation in Philadelphia where across 20 districts, families questioned about their residency or disenrolled from schools were disproportionately nonwhite.

“The enforcement is highly selective,” he said. If a school isn’t overcrowded, officials might not report a good student who fits in and doesn’t get in trouble, DeRoche said. “There is a lot of winking and nodding that goes along with this.”

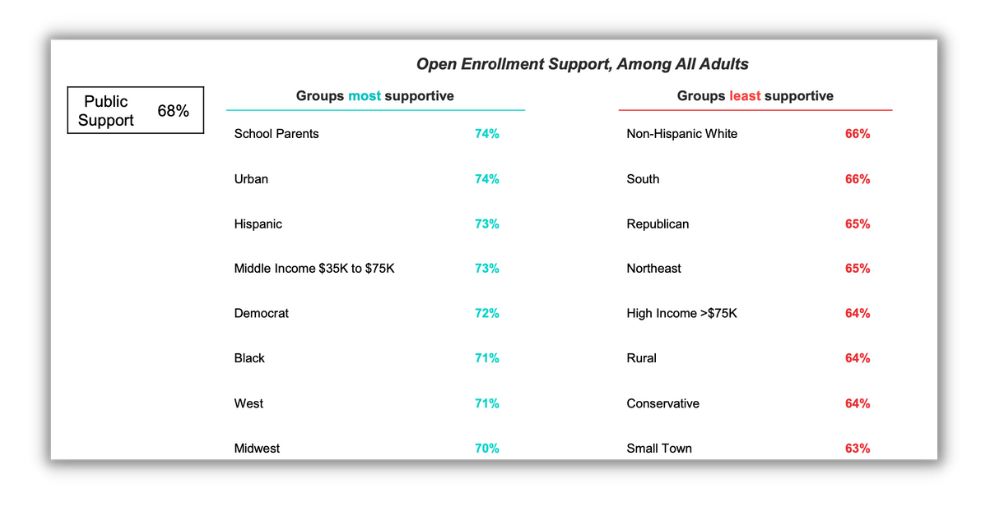

The authors urge states to repeal laws that target address sharing and refrain from using general statutes, like those against theft or perjury, to charge parents who lie about their residence. They also support open enrollment laws that allow families to choose a school in any district, regardless of where they live.

“When Good Parents Go to Jail” follows a 2021 Bellwether report that shows how district boundaries separate families by race and class, with low-income and minority parents often unable to attend a better school in a nearby district even when the district is within walking distance of their home.

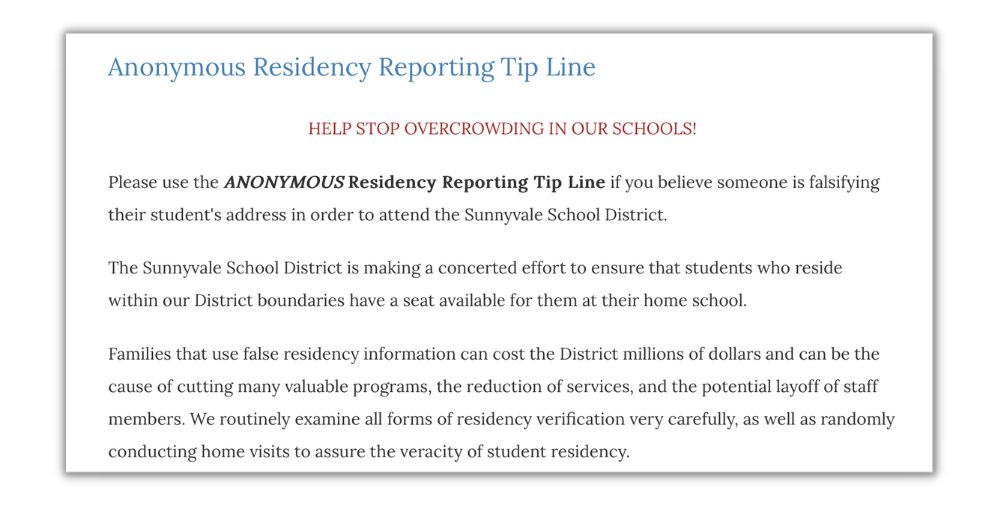

As long as attendance is tied to a student’s residence, DeRoche said, districts will be on the lookout for families trying to skirt the law.

“In some ways, districts have to enforce it because these coveted public schools are largely full,” he said.

VerifyResidence, a business that works with over 150 districts in multiple states, purchases U.S. Postal Service records and other databases to track down where students actually sleep at night, said Mike Auletta, a New Jersey-based private investigator who runs the company.

“It’s very difficult these days for a person in the wild to completely conceal where they live,” he said. “You’d be surprised how much of your data is for sale.”

With two young children and a wife who teaches special education at a public school, Auletta said he understands both sides of the issue. But districts are trying to protect their bottom line. Address sharing “strains budgets,” he said. “Now we don’t have enough teachers. Now we have 40 kids in a classroom.”

During the pandemic, which upended students’ living arrangements and caused educators to worry that some had stopped attending school anywhere, districts lightened up on enforcement. But now, more are conducting residency audits because “they’re done putting out fires,” he said.

“If I had had my way, I would have never gotten into trouble,” said Williams-Bolar, now a parent liaison for Available to All. “It’s very scary for an average parent that just wants their child safe and educated.”

Public opinion was split. Supporters argued she and her children were victims of an inequitable system, while critics said her punishment was justified. Similar debates over the ethics of address sharing show up on community message boards and sites like Reddit.

A Philadelphia man recently defended his actions in a commentary about school choice. “What the hell — the statute of limitations must be up: I lied, so my son could go to top-rated McCall Elementary School in Society Hill,” wrote Ryan Boyer. “And I make no apologies for it. We didn’t have financial capital at the time, but we had social capital.”

Parents confronted with such decisions sometimes contact Williams-Bolar to share their stories, but she understands why most are reluctant to speak publicly.

“Many parents are worried that they will be the next Kelley Williams-Bolar,” she said. “No one wants a mug shot.”

The idea can be just as controversial in dense urban areas where well-off families pay steep home prices to buy into neighborhoods with the most sought-after schools, DeRoche said.

“These are families with [Black Lives Matter] signs in their front yards, but they go apoplectic if you suggest that maybe this school shouldn’t be closed to families outside the zone,” he said. “[That] leads to the distorted home prices, which exacerbates the problem that only wealthy folks can attend the best public schools.”

Disclosure: Stand Together provides funding to Available to All, Bellwether and The 74. Andy Rotherham co-founded Bellwether and sits on The 74’s board of directors.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter